Celebrities and endorsements go together like bread and butter.

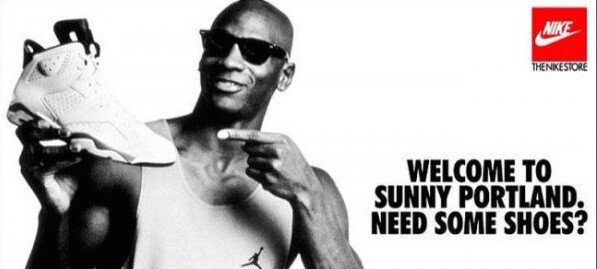

Nobody is surprised to see Michael Jordan touting a pair of sneakers in a magazine or on a billboard. Nobody expects him to wear Nike sneakers faithfully in his daily life.

He wears Nike in the ad because he is paid to do so. That is the implicit relationship between company, endorser and consumer.

But what if Michael Jordan tweeted about sneakers on his personal twitter account?

But what if Michael Jordan tweeted about sneakers on his personal twitter account?

What if he mentioned some brand other than Nike?

How could we know whether he was simply mentioning a product that he appreciated, or he was again paid to use his celebrity status to boost the value of a brand?

Precisely because he is a celebrity, we might just take it for granted that any product that appears on Michael Jordan’s twitter account comes with a high price tag.

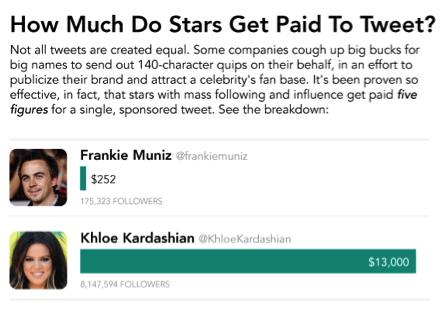

But what about non-celebrities? Or, pseudo-celebrities?

What about fashion bloggers who have tens of thousands of followers on their Instagram accounts?

When a fashion blogger endorses a designer, a pair of shoes, a new accessory, or other item of clothing, shouldn’t their followers be informed about any financial agreement between the brand and the blogger?

When a professional gamer posts a play-through of a new game on his YouTube channel, shouldn’t the audience know if he was paid to do so by the developer?

Wouldn’t that affect the weight that the viewer puts on that particular gamer’s review?

Those are just the kinds of questions that FTC attempts to answer in the newly released guidelines for social media marketers.

Those are just the kinds of questions that FTC attempts to answer in the newly released guidelines for social media marketers.

FTC released its first set of regulations on the topic of disclosure in social media marketing back in 2009.

Since that time it has been mostly hands-off in the enforcement of those regulations. In 2014, the agency sent a warning letter to Cole Haan, stating that its Pinterest contest in which participants were asked to pin pictures from the brand in exchange for entry into a $1000 sweepstakes, was at best, deceptive.

However, the 2015 guidelines make it clear: if money is changing hands, an in-ad disclosure is needed.

This golden rule is expected to be applied across all platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, blogs, Youtube, and even Twitter with its constricted 140-character max per tweet.

FTC even goes as far as to offer suggestions on how to work with the limited space by using words like “sponsored,” or “promotion” or even the #ad hashtag, all of which are short, concise disclosures that a particular form of media has been paid for.

Video sites such as YouTube and Dailymotion are also addressed in the new regulations.

Video sites such as YouTube and Dailymotion are also addressed in the new regulations.

According to FTC, a disclosure in the description of the video is not enough. Since videos are often shared or linked to through other sites, many viewers never see the description, or the disclosure.

To be as upfront and explicit as possible, FTC recommends that all video endorsements need to post their relationship to the sponsor at the beginning of the video and several times throughout, in order to avoid coming under the crosshairs for fraudulent practices.

It is not entirely certain when or how FTC will start its official crackdown, but from May 2015 forward, it is the responsibility of marketers to be aware of the regulations.

FTC has sent an unambiguous message: Social media marketers, you’ve been warned.